Five hidden secrets of NYC’s iconic bar the Ear Inn

The Ear Inn is one of the last truly old New York bars. Nestled at the western edge of Spring Street, it is the rare drinking establishment that has evaded the touch of both time and tourism. For over 200 years, the inn has served as a welcomed haven for New Yorkers who want to sip their beer in the company of good people, good music, and the inescapable presence of the city’s history.

The Ear Inn is currently co-owned by Martin Sheridan and Rip Hayman, who have stewarded this beloved establishment since the 1970s. On a sunny February afternoon, I had the pleasure of speaking with Sheridan about the inn’s history, its characteristics, and—of course—its secrets.

RECOMMENDED: Five hidden secrets of McSorley’s Old Ale House

A Riverfront Refuge

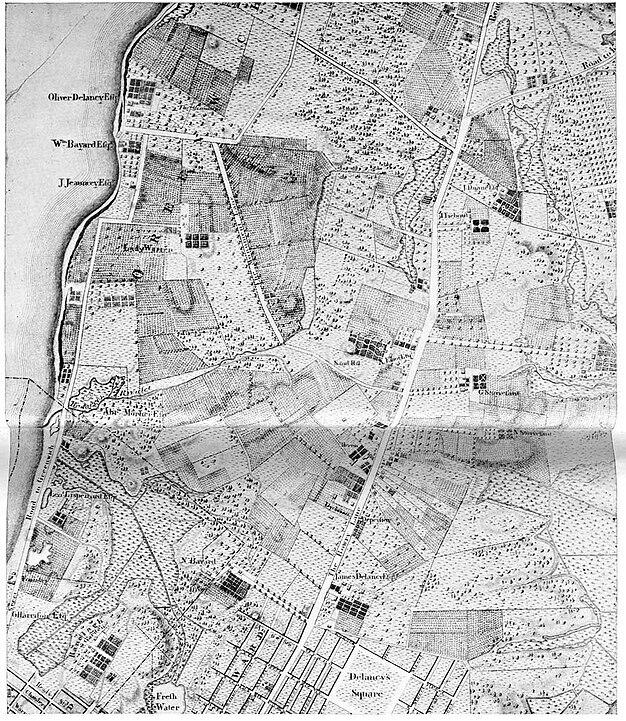

The ramshackle, two-and-a-half-story brick townhouse the Ear Inn calls home has been standing for roughly 250 years. It was constructed sometime in the 1770s by a wealthy tobacconist who is said to have crossed the Delaware alongside George Washington during the Revolutionary War.

The townhouse originally sat right on the water. The Hudson River ran a mere 5 feet to the left of the front stoop. Now, a block and a half of landfill separates the Ear Inn from its original neighbor. However, memories of the inn’s ties to the riverfront are hard to forget. When Sheridan and Hayman excavated the cellar, they found mounds of grey riverbed silt and the remnants of a long-forgotten pier laying peacefully alongside 18th-century bricks. Two hand-painted markers currently adorn a wooden panel next to the bar’s door: a line indicating where the Hudson River shoreline lay in 1766, and the highwater mark for the flooding caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Sandy’s extreme flooding cleared the height of the bar inside—but this didn’t faze a building that witnessed the creation of the United States, the Civil War, the consolidation of the five boroughs, and 9/11. A mere 12 hours later, Ear Inn had re-opened and was serving pints.

For its first century-and-a-half, the bar’s identity was inextricably linked with the river. In particular, it was a favorite for the sailors and longshoremen who worked the docks next door. Its popularity with this gruff and worldly community gave the bar its unofficial motto: “Known from coast to coast.” The bar became so well-known, in fact, that there was never a need to name it. Instead, it was simply known informally as “The Green Door,” and it didn’t gain an official name until Sheridan and Hayman took over.

Sheridan first came to the bar in the early 1970s. At the time, Sheridan was a roadie working for different bands as an equipment manager. After a long night of rehearsing nearby, Sheridan and a few band members found themselves looking for a spot to grab a drink and wind down. They noticed the warm glow of the inn’s neon sign—which then read “Bar”—and knocked on the door.

The man who answered told them, in no uncertain terms, they were not allowed in. Longshoremen only, he said. But after a successful charm offensive from Sheridan, the man relented. “Okay, you can come in for one drink,” he sighed. “But then get the fuck out of here.” As Sheridan and his friends scrambled inside, the bouncer shouted one final piece of advice: “If you need to use the bathroom … Go across the road.”

It May Be Misdated

When the brick townhouse was originally built, it was not located in New York City. Instead, its surrounding area was then part of the independent village of Greenwich, a rural exurb outside of the crowded city, which largely confined itself to the cluttered tip of the island until the early 19th century.

In 1817, New York’s urban sprawl finally subsumed Greenwich Village. This is the same year given for the establishment of the Ear Inn—“Est. 1817” is proudly displayed on the bar’s façade—because that’s when the city’s records indicate alcohol was first served out of the townhouse.

However, Sheridan is quick to point out that this is only because 1817 was the first year the townhouse legally fell within New York City’s jurisdiction, so it was the first year it could be included in the city’s records. In all likelihood, he said, the ground floor had been functioning as a tavern for far longer.

A Music Lover’s Haven

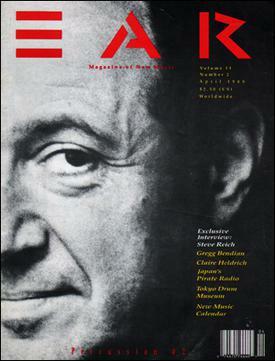

In the late 1970s, soon after Sheridan and Hayman had taken over, Hayman began running a music magazine he co-edited, Ear Magazine, out of the second floor. At this time, Sheridan and Hayden also decided their beloved bar finally needed a name, but one eluded them. That is—until they looked out the window.

The bar’s neon sign, which they believe is from the 1930s, simply read “Bar.” The building had been designated as a New York City landmark in 1969. This meant that to make any changes to the building’s façade, including the sign, Sheridan and Hayman would have to wade through rivers of red tape to get approval from the city’s Landmarks Commission.

But one day the two men realized they could keep the sign, avoid a bureaucratic nightmare, and rename the bar. All they required was a little spray paint. They painted over the curves of the “B” in “Bar” to form an “E,” and the establishment gained an official name for the first time in its 150-year history: the Ear Inn.

The Ear Inn has been a home to music lovers since Sheridan and Hayman took over. It proudly holds itself out as a music venue in addition to a bar. Sheridan informed me that the Earn Inn hosts the best jazz in the city—a Sunday night set performed in the back room by the “EARregulars.” The upstairs apartment can fit 20 to 30 people for cozier acoustic-style shows called “The Ear Up”.

Hayman’s son, Adrian, is a music producer, DJ, and carpenter who is currently renovating the upstairs apartment to install a sound booth and recording studio. Adrian, who goes by the stage name “Edo Lee,” is hoping to update the space to accommodate new “Tiny Desk-style” shows for local musicians. The goal is simple: “Keeping the old legacy going,” he said.

Spectral Stowaways

Like any proper bar, the Ear Inn has its ghosts.

Its most famous is Mickey. It is widely agreed that Mickey was a sailor—but that’s where the cohesion ends. Some stories say that Mickey lived in the apartment above the bar in the late 1800s. Others say he was just another customer from the bar’s rougher days: a sailor in the 1920s who spent his short time on shore lovingly looking into the bottom of a pint glass.

His cause of death is also disputed. One story says that on a moonless night, Mickey was drinking at the bar, as was his habit, when he decided to take a quick stroll outside. As he stumbled out into the street, he was struck by a car and killed. Another version claims that Mickey, desperate for a drink, disembarked his ship and headed straight for the Green Door. There, he was welcomed with a drink. Then a second. And another. And another. Mickey sat, glued to his barstool for hours, drinking into the wee hours of the morning. At some point, his earthly body simply gave out and he died sitting at the bar. It’s unclear at which point his drinking buddies noticed their companion lacked a pulse. But Mickey’s soul remained at the bar and there it stays to this day—an eternal patron.

Sheridan is not so sure about Mickey. After nearly 50 years of ownership, Sheridan is not convinced an otherworldly presence inhabits the barroom. Granted, that’s not to say he doesn’t believe in ghosts. “I come from Ireland,” he told me. “I was brought up on an old farm. Grew up with a bunch of stories of the banshees, and all that.” Nonetheless, he has not noticed any oddities in the barroom.

But upstairs? “Definitely,” Sheridan said. “They’re still here.”

As a former ghost tour guide, I feel confident in saying that the upstairs apartment certainly feels haunted. A steep set of stairs shoots upwards to a meandering warren of rooms. The floors slope at odd angles. Crooked sets of two or three stairs—and one subtly placed ladder—lead to small rooms nested on different levels.

Before it was an intimate music venue, the upstairs apartment functioned at one point as a brothel, a smuggler’s den, and a doctor’s office. It is filled with 19th-century furnishings and paraphernalia collected over the bar’s history. And it’s still yielding secrets: Hayman once discovered a revolver from the early 1900s hidden in the flue of the second-floor fireplace.

Whenever Sheridan’s upstairs at night, particularly when he’s alone, shadows dance at the edges of his vision. “Elongated shadows,” he clarified. Adrian Hayman, the music producer and carpenter, says when he works late upstairs, he hears footsteps in other rooms as well as doors opening and closing. He walks the floor to see who is still around—only to discover that he is alone.

Absolution Station

Robert Morgenthau, the longtime Manhattan District Attorney, was particularly fond of the Ear Inn. Several of Morgenthau’s campaigns began in the back room of the bar. As the city’s top prosecutor, the son of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Treasury Secretary, and the grandson of an ambassador, Morgenthau was, in many ways, the embodiment of New York’s patrician elite—a population which, in the 1970s and '80s, tended to avoid neighborhoods such as the inn’s.

These elitist apprehensions did not matter to Morgenthau. Like so many other New Yorkers before him, the allure of the Ear Inn transcended class and background. But this was not necessarily the case for his campaign donors. Sheridan chuckled as he remembered the looks of fear and confusion playing across the faces of New York socialites, reluctantly entering the Ear Inn to support another Morgenthau campaign, as they navigated its treacherously sloping floors in their high heels and fur coats.

“There, that’s something I haven’t told any other journalist before,” Sheridan said with a sly grin.

After nearly 30 years of patronage (and election victories), Morgenthau felt obliged to give something back to the Ear Inn. As the top prosecutor in the city, he decided to use his office to correct a longstanding injustice.

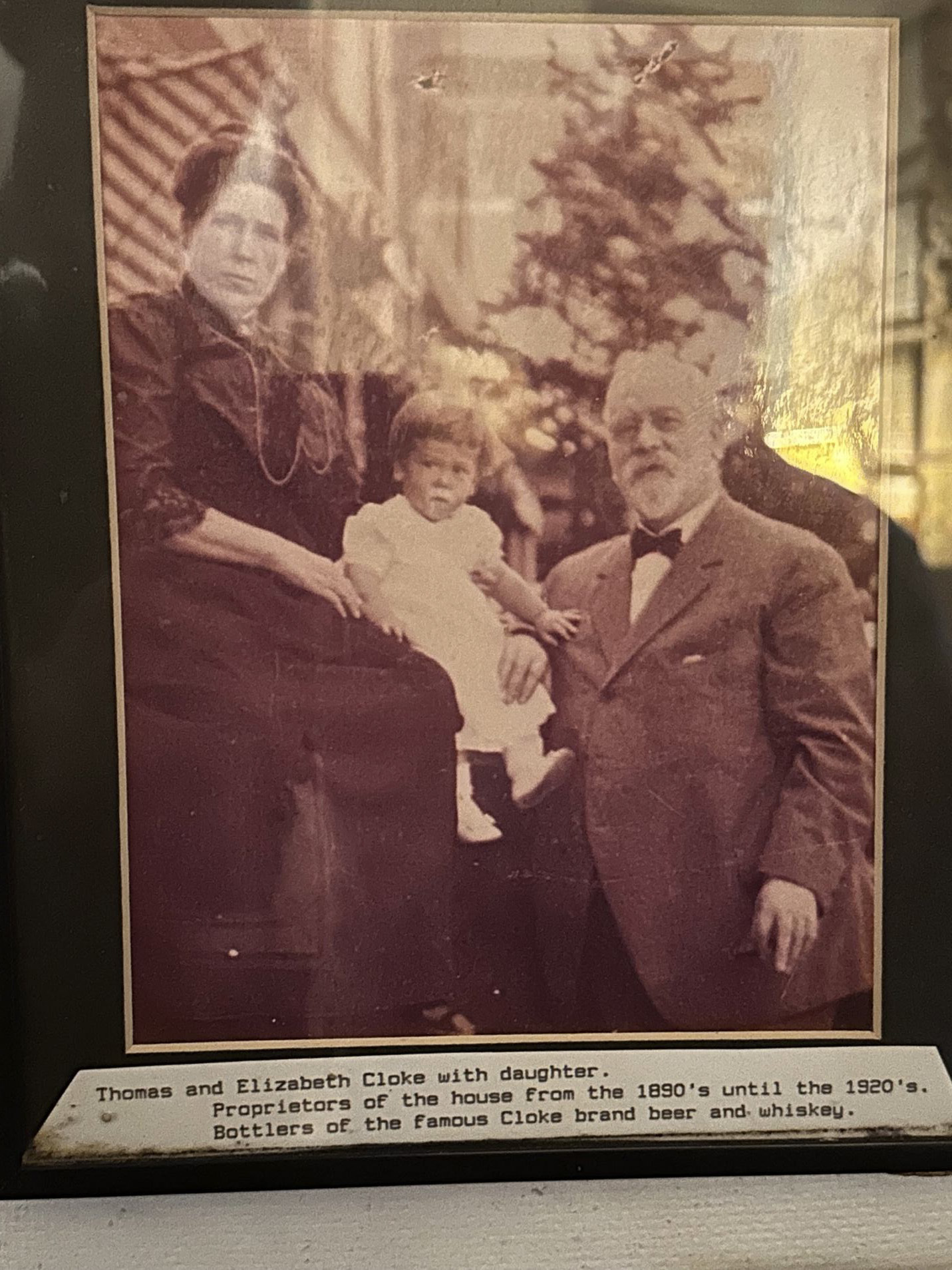

In 1905, the then-owner of the bar, a man named Thomas Cloke (who brewed his own beer in the backyard) was arrested for election fraud. Many of the details of Cloke’s case have been lost to history, but it appears he was never convicted for his alleged transgressions. Surely, however, the taint of such dubious charges sullied Cloke’s—and his bar’s—reputation.

In 2004, Morgenthau set to repair Cloke’s good name. In a letter, which is framed and hanging on the far left of the bar, is a signed Morgenthau letter witnessed by both Hayman and Sheridan giving notice that Thomas Cloke—99 years after his arrest—had been granted a full pardon by the city.

“The 1905 arrest record of Cloke’s public[ly] alleged but unproven improprieties have in no way been a detriment to the democratic process nor the public well being in the following years,” Morgenthau wrote. “Thus, I, District Attorney Robert Morgenthau, hereby absolve Thomas Cloke of further taint of any wrongdoing, and restore his good name for the sake of his descendants and the public which continues to enjoy his neighborhood establishment.”

No comments